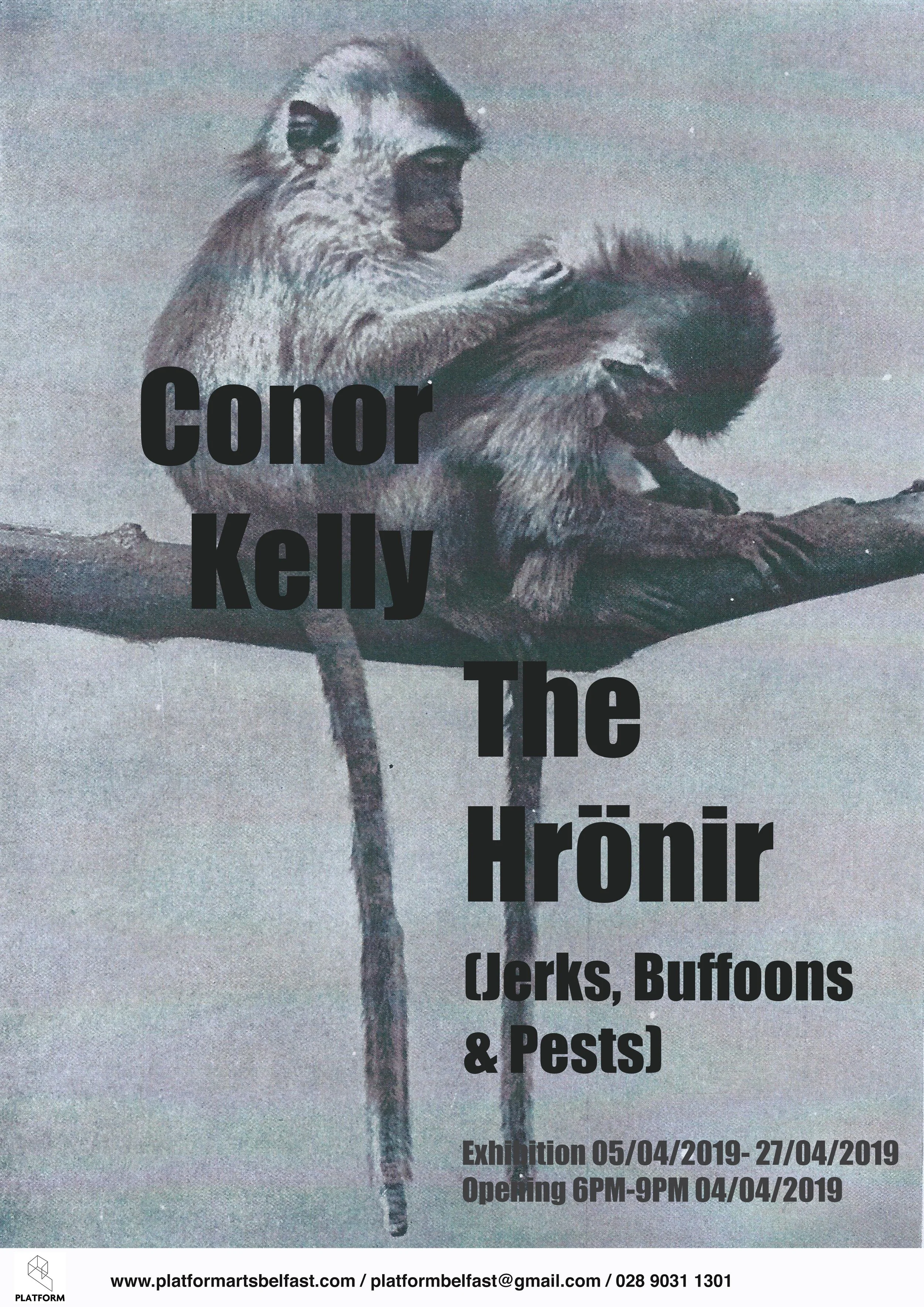

The Hrönir (Buffoons, Jerks & Pests)

Conor Kelly

Opening: 6PM-9PM 04/04/2019

Exhibition runs: 04/04/2019 – 26/04/2019

Platform Arts presents an installation of paintings by Glasgow-based artist Conor Kelly (born Cork 1980). ‘The Hrönir (Buffoons, Jerks and Pests)’ marks Kelly’s first solo exhibition in Northern Ireland since 2007 and brings together works that reference a variety of subjects including sacred Balinese monkeys and the ‘satanic panic’ that spread throughout Ulster between the years 1972-74. The paintings are presented in a dressed environment commissioned specially for the gallery space.

In recent years, Kelly’s practice has explored what he considers the ‘social life’ of painting, creating works that reference a miscellany of actors and events from natural, political and art histories.

The title of the exhibition refers to the mysterious and poetic objects that appear in Jorge Luis Borges’ short story Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius[1]. The hrönir are ’ideas, dreams and desires that are metaphorically projected onto the real world as solid, poetic objects’.[2] The hrönir are merely secondary objects that duplicate lost objects. ‘Like shadows in Plato's cave, they exist by virtue of their relation to prior (lost) entities; they are reflections (reproductions) of something that was once "real" but no longer is’[3].

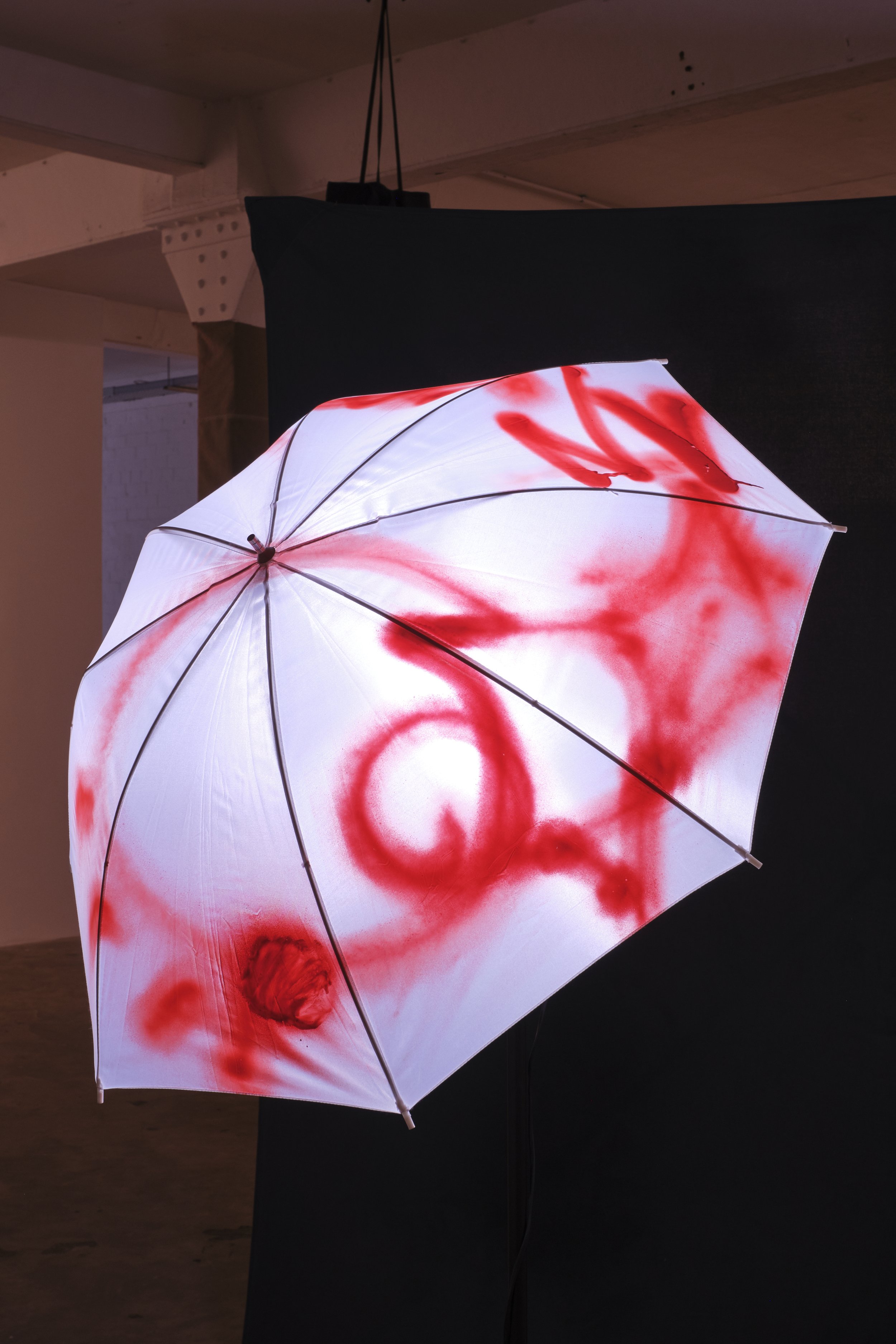

Kelly’s paintings are created without adopting a single ‘signature style’. They form several strands that employ representation and abstraction and use a range of supports – some stretched, some unstretched, on canvas and linen. The interaction of subject and surface plays on the potential of painting to act as a kind of enchanted technology[4]. The paintings collect Kelly’s reflections on the notion of sacred and profane territories in relation to the moral panic that spread throughout Ulster between 1972-74[5].

The dressing of the exhibition is part hommage to the psyops operations of British Army Intelligence Officer Colin Wallace (Born Randalstown 1943). Wallace admitted faking sites of alleged witchcraft and constructing several versions of the ‘Black Mass’ in the early 70s[6]. The threshold between the authentic technology of enchantment and a ‘faked’ or simulated other is play out in the different strands of painting and into the dressing of the gallery.

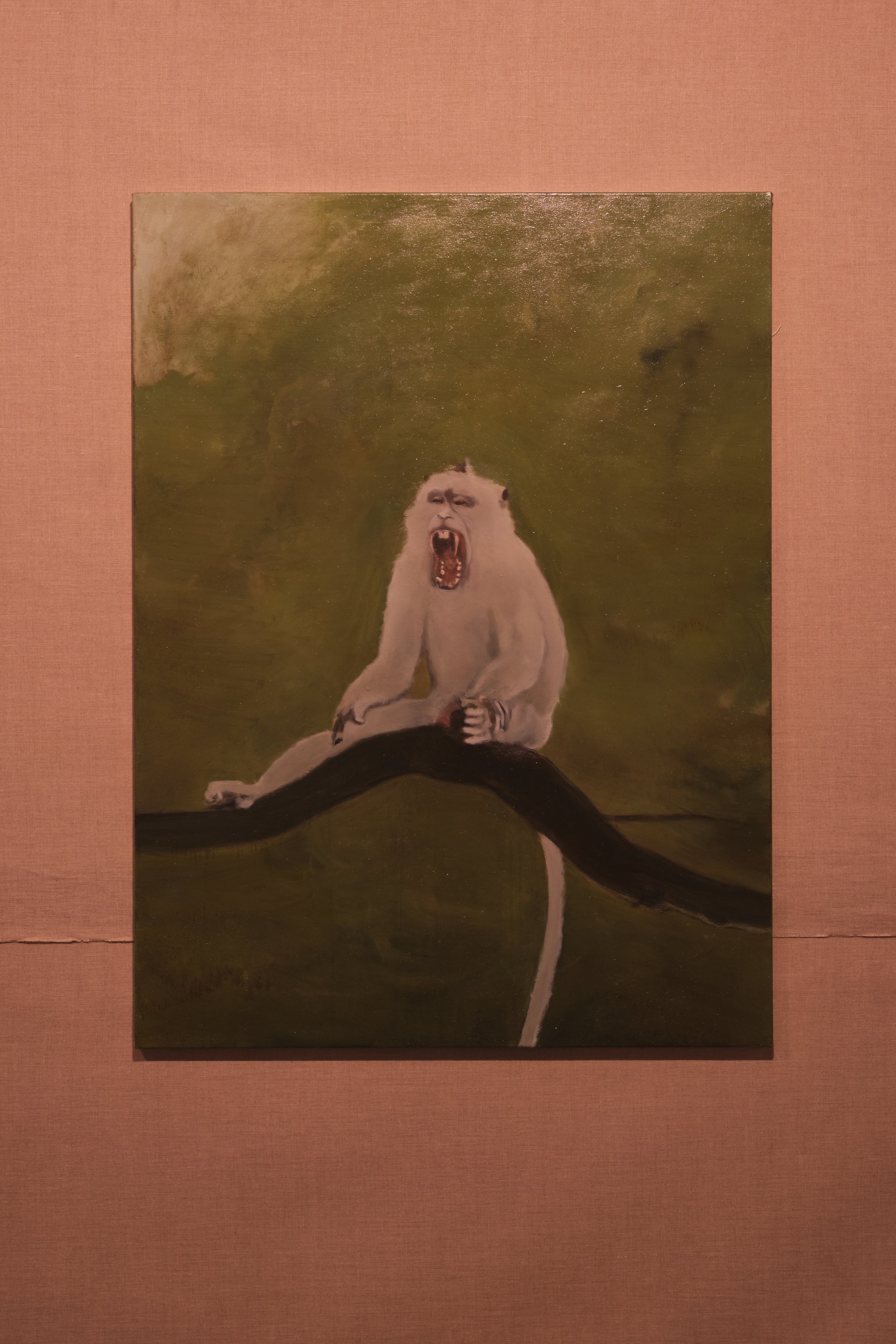

Among the animals represented in the exhibition is the long-tailed macaque (or crab-eating macaque) (Macaca fascicularis). The long-tailed macaque is treated as a sacred being at the Balinese site of Padangtegal Mandala Wisata Wanara Wana (sacred monkey forest sanctuary). Although worshipped in the forest and protected by law, if the monkeys stray beyond the perimeter of the forest they are treated as pests. This transformation amplifies and worries the meeting of the sacred and the profane. Kelly uses the image of the long-tailed macaque to embody the idea of the temporary elevation and suspension of symbolic value that still occurs in and around the contemporary art object. The paintings are, in part, a response to critic Isabelle Graw’s claim that painting functions as a ‘thinking subject’[7], and acts as a ‘highly valuable quasi-person’. The paintings in the exhibition try to anatagonise this subjectivity through their own kind of enchantment or ‘black magic’.

Taxonomy is dependent on shared characteristics, often through appearance. The macaque raises the question of its own taxon, its liveliness, its symbolic and monetary value, determined by the context or ‘protection’ of the gallery and the associated art world. The picture of the macaque attempts to operate beyond itself, charged by enchantment that remains uneasy and prone to disruption. This disruption affects some more established conventions in the art nexus, for instance, how we behave around art objects and vice versa. The picture attempts to de-stabilise some of the myths of modernity and opens up the question of what WJT Mitchell refers to as ‘vital signs’[8] in relation to pictures. When posing the question ‘what do pictures want?’ Mitchell looks to the ‘agency, motivation, autonomy, aura, fecundity’ of images, ‘not merely signs for living things but signs as living things.’ ’The Hrönir (Buffoons, Jerks and Pests)’ points to this classification of agency through the enchanted roots of art-practice and questions the potential of art objects to function in an increasingly de-materialised visual culture.

[1] Borges, Jorge Luis (1998) Collected Fictions. Trans. Andrew Hurley. London: Penguin.

[2] Fishburn, Evelyn (2008) Digging for hrönir: a second reading of "Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius" Variaciones Borges No. 25 (, pp. 53-67 https://www.jstor.org/stable/24880536

[3] Parkinson Zamora, Lois (2005) Swords and Silver Rings: Magical Objects in the Work of Jorge Luis Borges and Gabriel García Márquez in A Companion to Magical Realism (Ed Hart, Stephen M. & Wen-chin Ouyang).

[4] Gell, Alfred. (1994). The Technology of Enchantment and the Enchantment of Technology. In: J. Coote and A. Shelton, ed., Anthropology, Art and Aesthetics, 1st ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

[5] During this time, newspapers including the Armagh Guardian, Armagh Standard, Banbridge Chronicle, Ballymena Chronicle, Ballymena Observer, Belfast Telegraph, Carrickfergus Advertiser, Derry Journal, Dungannon Observer, East Antrim Times, Irish Independent, Irish News, Lurgan Mail, Mid-Ulster Observer, Mourne Observer, the Newsletter, News of the World, Republican News, Sunday World, Tyrone Courier, Ulster Gazette, Sunday Citizen, Sunday News, Sunday Press, Ulster Loyalist, Ulster Star, and WDA News repeatedly printed rumours of witchcraft in Ulster during the height of the Troubles. At the same time the British Army’s Psychological operations unit (Pysops) made a concerted attempt to provoke fear of dark magic among rural communities in Ulster. They intended to discredit paramilitarism by drawing connections to the taboo of satanic practice.

[6] Jenkins, Richard (2014) Black Magic and Bogeymen: Fear, Rumour and Popular Belief in the North of Ireland 1972–7 (Cork University Press) (p 69).

[7] Graw, Isabelle (2012) The Value of Painting: Notes on Unspecificity, Indexicality, and Highly Valuable Quasi-Persons in Thinking Through Painting: Reflexivity and Agency Beyond the Canvas (Berlin/New York, Sternberg Press.) (p 52)

[8] Mitchell, W.J.T. (2005) What do Pictures Want?: The Lives and Loves of Images, University of Chicago Press.

Images by Simon Mills (@photosbysi)